“Behind it is just… the remains of other pashkevilim.”

Jerusalem, May 20 – Residents of a heavily-Haredi neighborhood here began to suspect last week that a residential and commercial structure with a facade long-used as prime visual real estate for daily plasterings of announcements, bereavement notices, political messaging, advertisements, and other adhesive content consists not of stones or concrete to which the papers cling, but of the papers themselves, layer upon layer for more than a century.

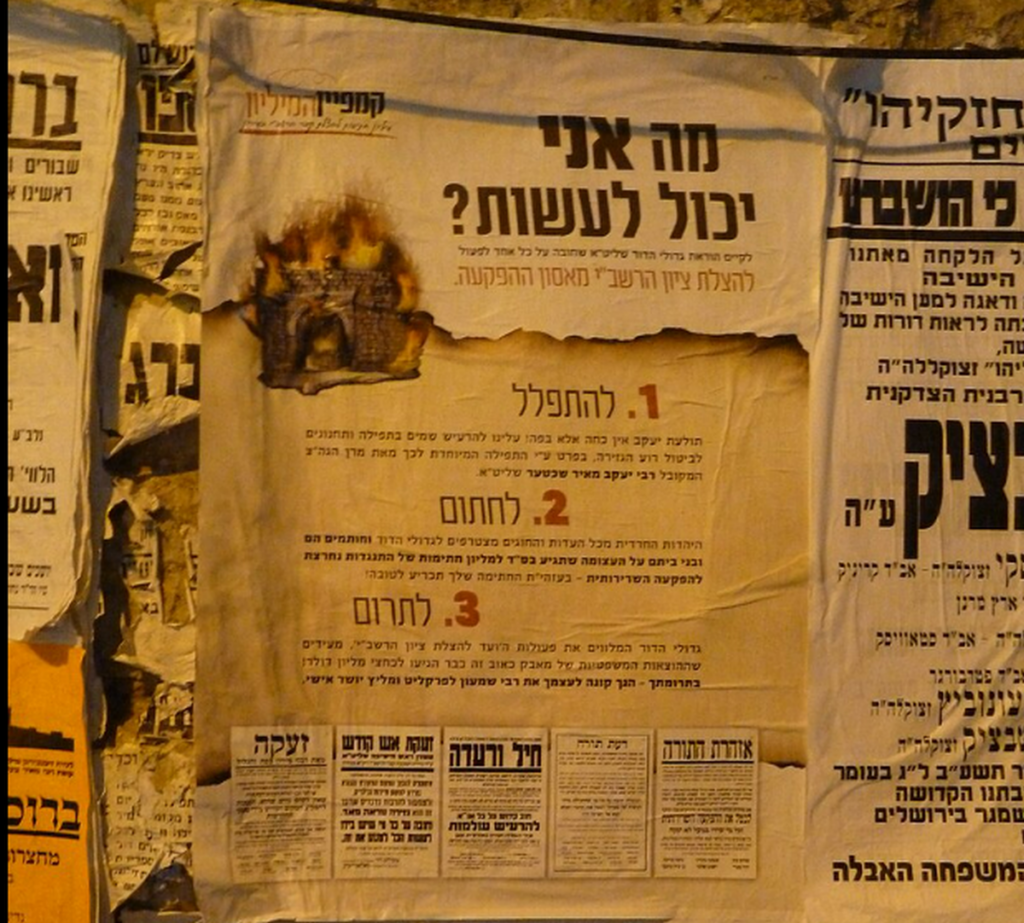

Pashkevilim – broadside paper signs posted by law only on official boards for the purpose, but in practice adorning every vertical surface in many “ultra-orthodox” enclaves – appear to compose the entirety of a building in the area of Meah She’arim, according to observers. No one asked could recall ever seeing a stone, brick, concrete, or other material behind the pashkevilim, leading passers by and neighbors to speculate that the disused, one-story edifice just off the neighborhood’s eponymous main street does not, in fact, have a structure beyond the pashkevilim themselves.

“Every once in a while a chunk of the old posters falls off,” explained Shaina Moskowitz, 30, who lives around the corner. “Behind it is just… the remains of other pashkevilim. It seems to account for the entire thickness of the wall.”

“No one can actually tell you what this building is or was,” explained another passerby who gave his name as Shneur. “I’ve lived here for fifty years, and it looks more or less like it did way back when.”

Municipal records offer little clarity; many lots went unregistered through lackluster Ottoman, and then British, administrations, and when the nascent State of Israel assumed governance in 1948, the area’s staunch anti-Zionist culture minimized cooperation with municipal officials and institutions. Haredi culture, which discourages use of many modern communications media, still relies in many ways on the equivalent of posters in the town square.

The Yiddish-cum-Hebrew term “Pashkevil” derives from a practice in late-renaissance Rome to post political or social commentary on the remains of a ruined ancient statue called the Pasquino. While confined to Rome’s literary classes, the practice spread easily to the much-more-literate Jewish communities of Europe, who brought it with them in successive waves of migration to Ottoman Palestine in the nineteenth century, both before and during the advent of political Zionism. The perpetuation of the practice serves the dual purpose of informing the Haredi population of developments political, religious, commercial, communal, and social, and of demonstrating continued adherence to avoidance of modern means of communication associated with licentiousness, time-wasting, and intellectual atrophy.

Please support – our work through Patreon.

Buy In The Biblical Sense: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0B92QYWSL